The World Health Organization (WHO) declared it on Saturday. the ongoing worldwide outbreak of monkeypox, a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC), announced Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghrebeyesus.

Tedros made the statement despite a lack of consensus among WHO emergency committee members on the monkeypox outbreak. It is the first time that a leader of a UN health agency has taken such a decision.

What did Tedros say?

“We have an outbreak that has spread around the world rapidly through new modes of transmission about which we understand too little and that meets the criteria of international health regulations,” Tedros said.

“I know that this has not been an easy or straightforward process and that there are divergent opinions among the members” of the commission, he added.

“While I am declaring a public health emergency of international concern, for now this is an outbreak that is concentrated among men who have sex with men, particularly those with multiple sexual partners,” Tedros continued. “This means that this is an outbreak that can be stopped with the right strategies in the right groups.”

How has the outbreak spread?

The current outbreak began in May, with 20 cases reported in Britain on May 20, mostly among gay men.

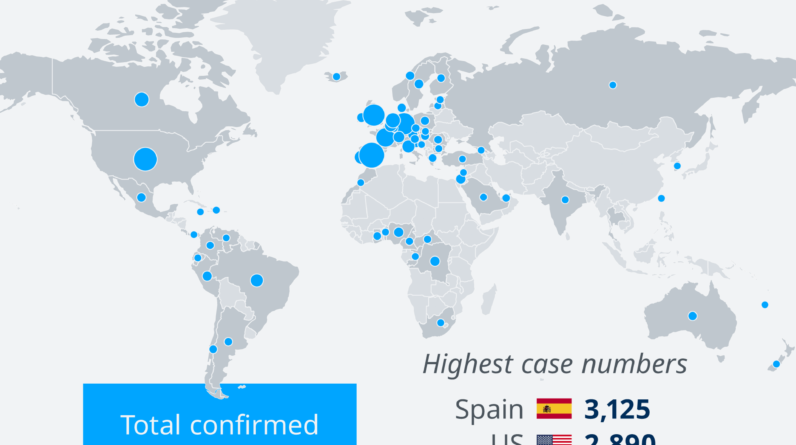

Since then, the outbreak has grown to nearly 16,000 cases in 75 countries, Tedros said. CDC data in the US indicates that in a single day, July 19-20, the number of confirmed cases jumped from 14,511 to 15,378. The current outbreak is centered in Europe.

Since July 14, Bermuda, Thailand, Serbia, Georgia, India and Saudi Arabia have reported their first cases, adding to the 73 countries where the current outbreak has been detected.

As the outbreak continues to grow, epidemiologists are divided over whether the WHO’s decision was the right one. The meeting was the second time the emergency committee had been convened, following a meeting on June 23 when it decided the outbreak had not reached that threshold.

“It’s a difficult decision for the committee,” said Dr Jimmy Whitworth, professor of international public health at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

“In some ways, it meets the definition: it is an unprecedented widespread outbreak in many countries and would benefit from greater international coordination.

“On the other hand, it appears to be an infection for which we have the necessary tools for control; most cases are mild and the mortality rate is extremely low,” Whitworth told DW.

What is a PHEIC?

The designation of public health emergency of international concern is the WHO’s highest alert level. It is based on international health regulations established in 2005, to define the rights and obligations of countries in the management of cross-border public health incidents.

WHO defines a PHEIC as “an extraordinary event that is determined to constitute a public health risk to other states through the international spread of disease and that may require a coordinated international response.”

The WHO further explains how this definition implies a serious, sudden, unusual or unexpected situation; it has public health implications beyond the border of an affected country and may require immediate international action.

WHO international health emergency declarations

A public health emergency

In the event of a deadly disease outbreak, a panel of World Health Organization (WHO) experts can declare a “public health emergency of international concern,” or PHEIC, to trigger global action. Since the procedures for declaring a PHEIC were implemented in 2005, the WHO has done so only six times. Let’s take a look back at the previous instances.

WHO international health emergency declarations

Coronavirus

In 2020, the WHO declared a global health emergency over a novel coronavirus that originated in China but spread to several countries around the world, including Germany. Officials said the declaration was due to “the potential for this virus to spread to countries with weaker health systems that are not prepared to deal with it.”

WHO international health emergency declarations

Swine flu

The 2019 H1N1 influenza (also known as swine flu) pandemic, which began in Veracruz, Mexico, is estimated to have killed up to 284,500 people. That’s more than 15 times the original estimate of 18,500. The UK-based Lancet Infectious Diseases journal, however, has suggested that the actual death toll could have been as high as 579,000. Here, a Chinese doctor prepares a vaccine.

WHO international health emergency declarations

Ebola in West Africa

The Ebola virus outbreak in Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia between 2013 and 2016 was deadlier than all other Ebola outbreaks combined, killing at least 11,300 people. A 2018 study by the Oxford-based Journal of Infectious Diseases estimated that the outbreak cost the three countries involved up to $53 billion (€48 billion).

WHO international health emergency declarations

Poliomyelitis

In 2014, Pakistan’s failure to curb the spread of polio led the WHO to declare the resurgence of the disease a PHEIC. The warning covered Pakistan, Syria and Cameroon. At the time, Pakistan accounted for more than a fifth of the 417 reported cases worldwide.

WHO international health emergency declarations

Zika

In 2016, the Zika virus was declared a PHEIC by the WHO. The outbreak was identified in Brazil in 2015. The disease eventually spread to 60 countries, with 2,300 confirmed cases of microcephaly among newborns. Microcephaly causes birth defects such as abnormally small heads, which can lead to developmental problems.

WHO international health emergency declarations

Ebola in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)

In July 2019, after its fourth meeting since the DRC outbreak began, the WHO Ebola Emergency Committee declared it a PHEIC. As of 14 January 2020, the WHO had confirmed 3,406 cases of Ebola in the DRC, including about 2,236 deaths since the outbreak began in August 2018. The WHO estimates that the disease could cost the DRC up to to 1 billion dollars (900 billion euros). .

Who decides on a PHEIC?

The WHO emergency committee on monkeypox provided advice on the disease to WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, but was unable to reach a consensus.

WHO’s emergency committee on monkeypox is made up of 16 members and is chaired by Jean-Marie Okwo-Bele of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the agency’s former director of vaccines and immunization.

Other committee members include epidemiologists and disease experts from around the world.

What are the advantages and criticisms of PHEICs?

The purpose of a PHEIC is to focus attention on acute health risks that have the potential to spread internationally and threaten people worldwide.

They aim to help mobilize and coordinate information and resources, both nationally and internationally, for prevention and response purposes.

In practice, declaring a PHEIC can end up causing a financial burden on the country dealing with the epidemic, especially if travel and trade are curtailed. In fact, some countries are reluctant to share public health data in the event of an outbreak for fear of such measures.

Critics of the PHEIC system point out that an emergency is only declared when an event has begun to spread internationally, indicating that it has already reached an acute level. Some have called for various intermediate stages of alarm.

In the case of COVID-19, for example, a PHEIC was only declared in late January 2020, after two meetings earlier in the month had decided against such a move, and several weeks after Beijing had adopted containment measures.

Researchers have found that too many countries take a “wait and see” approach to these declarations, ignoring them until it’s too late, as with COVID-19.

“People weren’t listening,” WHO emergencies director Michael Ryan said on the second anniversary of the COVID-19 pandemic declaration. “We were ringing the bell and people weren’t acting.”

These statements are subject to too much political pressure, some argue. Others criticize that the emergency committee’s justification has tended to be opaque or contradictory.

What PHEICs have there been in the past?

To date, the WHO has declared a PHEIC six times, all due to viral outbreaks:

January 2020 for COVID-19, declared when the virus was first detected outside of China. This eventually became a persistent global pandemic in July 2019 for Ebola, for the second time, linked to the February 2016 outbreak in eastern DRC of Zika, which began in Brazil and mainly affect Latin America in August 2014 for Ebola, for an outbreak in West Africa that also spread to Europe and the USA in May 2014 for polio, after an increase in the spread of “wild polio” and vaccine-derived virus in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Nigeria. Besides the one for COVID-19, this is the only PHEIC still in force. 2009 by the H1N1 flu or “swine flu”, which started in Mexico and spread around the world

Three outbreaks have been considered but not declared PHEIC. These include the deadly MERS outbreak first identified in Saudi Arabia in 2013.

what happens next

“WHO will continue to do everything possible to help countries stop transmission and save lives,” Tedros told a news conference in Geneva on Wednesday.

Although highly effective vaccines against monkeypox exist, production would need to be increased to meet demand

Testing and vaccination are sharp tools in the fight against monkeypox, although Tedros also said information was key. First, public health officials must engage constructively with at-risk communities, experts say.

Some experts have sounded the alarm of a possible pandemic based on the recent big jump in the number of cases.

“From what is known, we think it is unlikely to spread widely in the general population,” said public health professor Whitworth. “For those reasons, I don’t think this will become a widespread epidemic.”

Edited by: Andreas Illmer, Anne Thomas

[ad_2]

Source link