ExplainSpeaking-Economy is a weekly newsletter from Udit Misra, delivered to your inbox every Monday morning. Click here to subscribe

This week the Indian state of Karnataka goes to vote. Voting will take place on May 10 and the results will be counted on May 13. This is a crucial election not only because Karnataka is one of India’s largest and most influential states, but also because it could set the tone for a series of crucial elections in the coming months leading up to the national general election in early 2024.

Here’s a quick look at some of Karnataka’s key economic and social metrics. The idea is not just to see how Karnataka compares to the Indian average and some of the other big states, but also to look at how it has been shaping up over the last four to five years. Of course, the last state election in Karnataka took place in May 2018, so data for the financial year ending March 2018 provides a good backdrop for comparisons.

#1: Size of the economy or gross domestic product of the State (GDP)

GSDP is the market value of all goods and services produced in a state. It is similar to the GDP measure for India as a whole. The larger the GDP, the larger the size of a state’s economy.

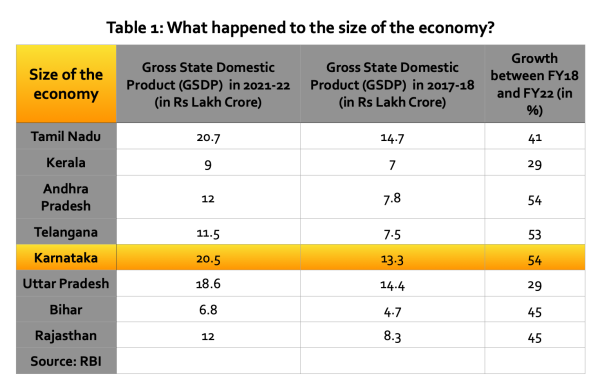

Table 1 provides GSDP data for various states for two financial years: 2021-22 and 2017-18. The source is RBI’s Statistical Manual of Indian States which was released in November last year. The choice of states has been made based on the availability of data. For example, Gujarat and Maharashtra, two of the largest state economies, are missed because relevant data was not available.

Table 1: What happened to the size of the economy?

There are three ways to read the data provided in Table 1.

One is to look at the first column and find out how Karnataka compares in size to some of the other big states.

Two is to look at where Karnataka (or any of the other states mentioned) was five years ago.

Three is to look at the extent to which Karnataka’s GSDP has grown over the years.

Of the economies mentioned, Karnataka seems to have grown better than most. It is important to note that the period in question includes the Covid shock. By the end of FY22, Karnataka had almost caught up with Tamil Nadu and at this rate, it might overtake its southern neighbor when data for FY23 (year ending March 2023 ) are available for all states.

Andhra Pradesh and Telangana have also witnessed a similar increase in the size of their economies, while states like UP and Kerala have lagged behind.

#2: Size of the economy in “real” terms.

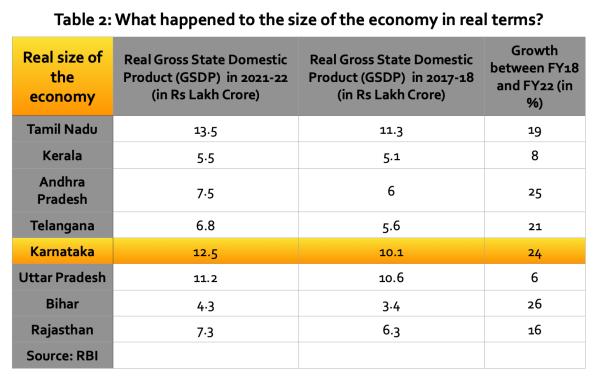

The data in Table 1 provide nominal figures; that is, the data includes the effect of inflation. But what would happen to the size of the economy if the effect of inflation were removed?

Table 2 gives the answer to this. GSDP is reduced for all states when we remove the effect of inflation. And while Karnataka remains one of the best performers (within this group) in terms of percentage growth, it remains almost as far behind Tamil Nadu in absolute terms as it was four years ago.

Table 2: What happened to the size of the economy in real terms?

Table 2: What happened to the size of the economy in real terms?

A somewhat surprising but noteworthy point is the growth of Bihar’s economy, the highest among all the states considered here.

#3: Income per capita in real terms

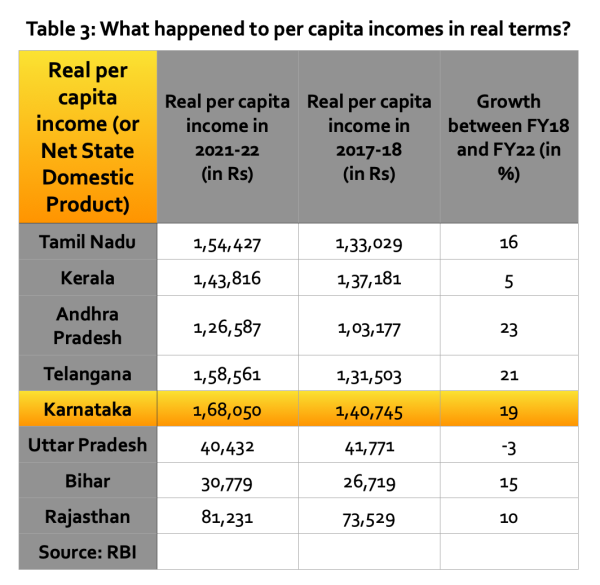

While the overall size of the economy is an important measure, what often determines prosperity is a state’s average economic output or income. Table 3 provides details of what happened to “real” per capita income in Karnataka and elsewhere between FY18 and FY22.

Table 3: What Happened to Per Capita Income in Real Terms?

Table 3: What Happened to Per Capita Income in Real Terms?

Despite falling behind Tamil Nadu in overall size, Karnataka remains at the top in per capita terms. Again, per capita income growth in Karnataka is behind only Andhra and Telangana.

Notably, Uttar Pradesh is the only state in this table that has seen its per capita income decline over these four years. That the ruling party and the prime minister were re-elected with a resounding majority puts this data and any such analysis into perspective.

#4: Inflation rate

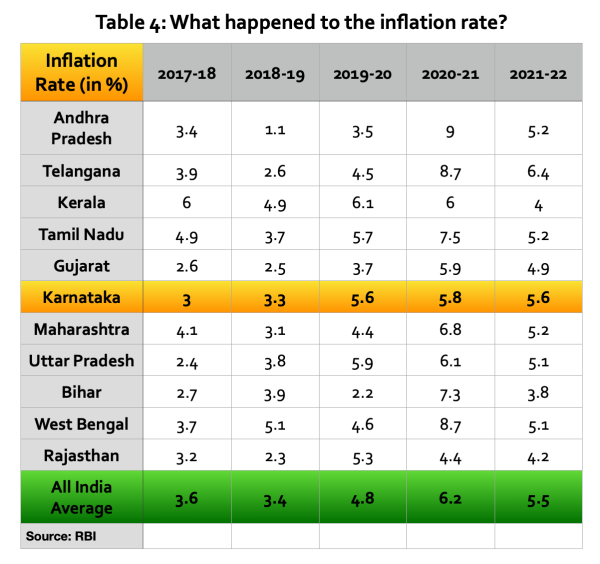

The inflation rate has been a major concern in recent years. Table 4 gives a snapshot of how Karnataka fared in each of the past years.

Table 4: What Happened to the Inflation Rate?

Table 4: What Happened to the Inflation Rate?

In most years, Karnataka performs better than other southern states as well as the Indian average. Only Rajasthan, Gujarat and Bihar seem to have done better than Karnataka. Bihar’s lower inflation rate explains why its performance stood out when considering the size of the economy in real terms in Table 2.

#5: Unemployment rate

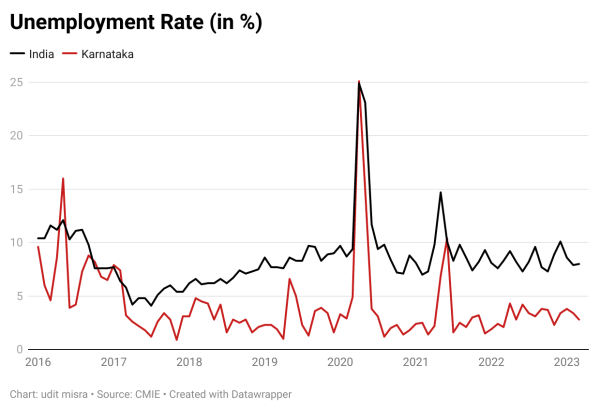

CHART 1 represents the unemployment rate of India and Karnataka. The data comes from the CMIE.

Chart 1: Unemployment rate (in %) in Karnataka vs India.

Chart 1: Unemployment rate (in %) in Karnataka vs India.

Barring the two waves of Covid, Karnataka’s unemployment rate remained much lower than the national average. At first glance, this result will line up well with other measures like GSDP growth.

However, the unemployment rate is a poor metric for measuring job hardship in a country like India. This is because the unemployment rate only indicates the number of people who did not get a job while looking for one. Under normal circumstances, this measure is good enough. But in India, the number of people looking for work continues to decline. As such, the unemployment rate often underreports job stress because it fails to capture the number of people who became discouraged and stopped looking for work.

That’s why it’s best to look at the next variable to understand precisely what’s happening with jobs in the state.

#6: Occupancy rate

Simply put, the employment rate indicates the number of people employed in the state as a percentage of the total working-age population (that is, the population over 15).

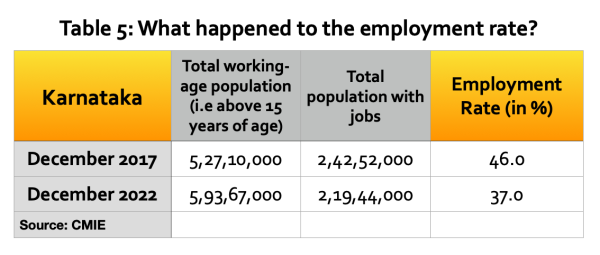

Table 5 lists the latest publicly available data from the CMIE.

Table 5: What happened to the employment rate?

Table 5: What happened to the employment rate?

As of December 2017, out of a total working age population of 527 lakhs, Karnataka had around 242.5 lakh people in employment. That’s an occupancy rate of 46%. That wasn’t a high enough number to begin with. However, in December 2022, while the working-age population increased by another 67 lakhs, the total number of employed people, instead of increasing, actually decreased by more than 23 lakhs.

The significantly lower employment rate shows that while the size of the state’s economy is expanding, far from creating new jobs, that growth is coming with fewer jobs. This also implies that higher per capita incomes are only of academic importance, as they essentially hide the state’s economic stress.

#7: Health and gender metrics

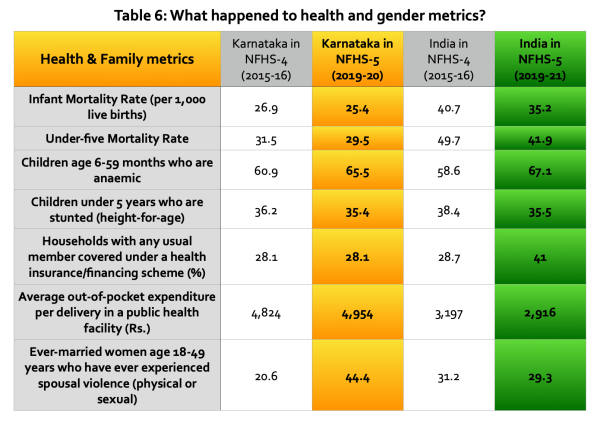

Table 6 provides these data for Karnataka and the all-India average for the last two rounds of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS).

Table 6: What Happened to Health and Gender Metrics?

Table 6: What Happened to Health and Gender Metrics?

At first glance, on most NFHS metrics (and there are 131), Karnataka does much better than the all-India average.

The infant mortality rate and the under-five mortality rate in Table 6 make this clear.

However, there are some metrics where, despite being one of the wealthiest states, Karnataka shows the same stagnation seen in all-India data. The proportion of stunted children is an example.

Here are some variables where Karnataka lags behind the India average. For example, the average out-of-pocket expenditure per delivery in a public health facility is not only higher than the Indian average, but also increasing, a stark contrast to the all-India trend.

Do economic and social indices matter when voting? Share your views at udit.misra@expressindia.com

Until next week,

kanakanmani

[ad_2]

Source link