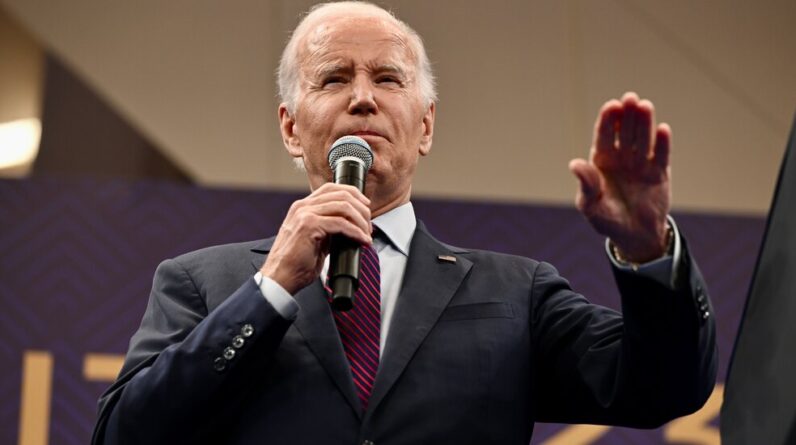

After weeks of tense wrangling between the White House and House Republicans, the fiscal deal reached Saturday to raise the debt ceiling while reining in federal spending bolsters President Biden’s case that he is the only figure still bipartisanship can do in a deeply partisan era.

But it comes at the cost of upsetting many in his own party who have little appetite to meet Republicans in the middle and think the president can’t help but give too much away in an eternal and ephemeral search for consensus. And now he will test his influence over his fellow Democrats who will need to pass the deal in Congress.

The deal in principle he reached with President Kevin McCarthy represents a case study in Mr. Biden’s governing for the presidency, underscoring the fundamental strain of his leadership since the 2020 primaries, when he outlasted progressive rivals. to win the Democratic nomination. Mr. Biden believes in his bones to get across the aisle even at the expense of some of his own priorities.

It has proven this repeatedly since opening two-and-a-half years ago, although skeptics doubted that inter-match accommodation was still possible. Most notably, he pushed through Congress a bipartisan public works program allocating $1 trillion to build or repair roads, bridges, airports, broadband and other infrastructure; legislation expanding treatment for veterans exposed to toxic burn waste; and an investment program to boost the country’s semiconductor industry, all approved with Republican votes.

This is not, however, a time when bipartisanship is valued the way it was when Biden moved into the Senate in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. His desire to position himself as the leader who can bring together a deeply divided country is at the heart of his case for a second term next year. But it conflicts with the interests of many Democrats who see more political benefit in standing firm against former President Donald J. Trump’s Republican Party and prefer to draw a sharper contrast for their own elections in 2024 when they hope to regain the Chamber

“The deal represents a compromise, which means not everyone gets what they want,” Biden said in a written statement issued Saturday night when the deal was announced. “This is the responsibility of governing.”

Most importantly, from Mr. Biden’s point of view, the deal averts a catastrophic domestic default that could have cost many jobs, plunged stock markets, jeopardized Social Security payments and made the economy falters. It’s based on the assumption that Americans will appreciate mature leadership that doesn’t gamble with the nation’s economic health.

But many on the political left are aggravated that Mr. Biden, in their view, has given in to Mr. McCarthy’s hostage-taking strategy. The president who said the debt ceiling was “non-negotiable” ended up negotiating it after all to avoid a national default, barely bothering with the fiction that the spending limit talks were of any separately

Liberals were pushing Mr. Biden to stiff the Republicans and short-circuit the debt ceiling altogether by claiming the power to ignore it under the 14th Amendment, which says the “validity of the public debt” of the federal government “shall not will question.” ” But while Mr. Biden agreed with the constitutional interpretation, he concluded that it was too risky because the nation could still default while the issue was litigated in court.

And so, to the chagrin of his allies, the negotiation of the last few weeks was entirely in Republican terms. While details were still emerging this weekend, the final deal did not include Biden’s new tax initiatives, such as higher taxes on the wealthy or expanded insulin rebates. The question was basically what part of the Limit, Savings and Growth Act passed by House Republicans last month the president would accept in exchange for raising the debt ceiling.

But Mr. Biden managed to significantly strip the Limit, Save and Grow Act from what it originally was, much to the consternation of conservative Republicans. Instead of raising the debt ceiling for less than a year and imposing hard limits on discretionary spending for 10 years, the deal ties them together so that the spending limits last only two years, just as the increase in debt ceiling While Republicans insisted on predicting caps on a baseline of 2022 spending levels, the appropriations adjustments will effectively make it equivalent to the more favorable 2023 baseline.

As a result, the deal will cut projected spending over the decade to just a fraction of what Republicans sought. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that the limits passed by House Republicans last month would have cut $3.2 trillion in discretionary spending over 10 years; a rough calculation by the New York Times suggests that the deal reached by Mr. Biden and Mr. McCarthy could cut just $650 billion.

Moreover, while Mr. Biden did not advance many new Democratic policy goals in the deal with Mr. McCarthy effectively shielded most of his accomplishments from the first two years of his presidency from Republican efforts to dismantle them.

The Republican plan called for revoking many of the clean energy incentives that Mr. Biden included in the Inflation Reduction Act, eliminating additional funds for the Internal Revenue Service to pursue wealthy tax cheats and blocking the president’s plan to forgive $400 billion in student loans for millions of people. americans None of this was in the final package.

Indeed, the IRS provision provides an example of Mr. Biden’s arrangement. As a token concession to Republicans, he agreed to cut about $10 billion from the additional $80 billion previously allocated to the agency, but most of that money will be used to avoid deeper cuts in discretionary spending sought by Republicans.

One of the most sensitive areas for Mr. Biden’s progressive allies was the Republican insistence on imposing or expanding work requirements on recipients of social safety net programs, including Medicaid, food assistance and welfare payments for families. Mr. Biden, who supported welfare work requirements in the 1990s, initially signaled his openness to considering Republican proposals, only to face fierce pushback from Democrats.

On Friday night, even as the deal was coming together, the White House issued a scathing statement accusing Republicans of trying to “take food out of the mouths of hungry Americans” while preserving cuts to taxes for the rich, on the one hand with the aim of reassurance. restless liberals as attacking hardline conservatives.

The final agreement between Mr. Biden and Mr. McCarthy does not include work requirements for Medicaid, but raises the age for people who must work to receive food assistance through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, to 54 while eliminating requirements for veterans and homeless person. The deal moderates Republican provisions to expand work requirements for Temporary Assistance to Needy Families.

The challenge now for Mr. Biden is to sell the commitment to his fellow Democrats. In the same way that Mr. McCarthy knows he will potentially lose dozens of Republicans disappointed by the tweaks he made, the president hopes many in his own party will also vote against the final product. But he must deliver enough Democrats to offset GOP defections to forge a bipartisan majority.

Minutes after the deal was announced Saturday night, the White House sent briefing materials and talking points to all House Democrats and followed up Sunday with phone calls. “Negotiations require give and take,” the talking points said. “Nobody gets everything they want. That’s how divided government works. But the president successfully protected his and the Democrats’ core priorities and the historic economic progress we’ve made over the past two years.”

Mr. Biden has been here before. As vice president, he was President Barack Obama’s chief negotiator in several tax showdowns, but he so aggravated fellow Democrats who thought he was giving too much that Sen. Harry M. Reid of Nevada, then the Senate leader, banned indeed Mr. Biden in 2013 from negotiations on an increase in the debt ceiling.

Throwing a vice president out of the room, of course, is one thing. Mr. Biden is now the president and the leader of his party facing a year of re-election. It’s his room. And he’s managing it on his own terms, whether he likes it or not.

[ad_2]

Source link