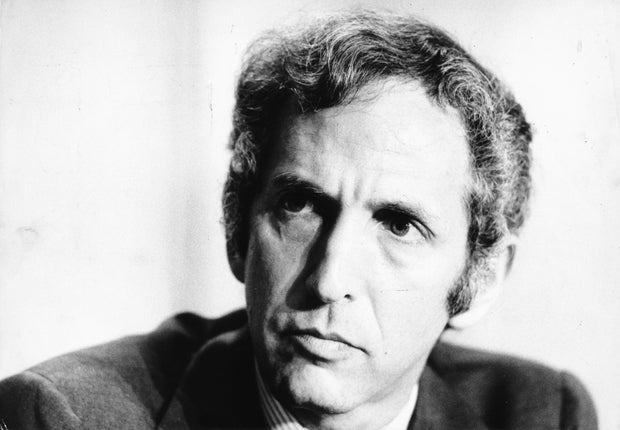

Daniel Ellsberg, the anti-war activist who copied and leaked documents revealing secret details of US strategy in the Vietnam War who became known as Pentagon Papers, has died, his family confirmed in a statement to CBS News on Friday. He was 92 years old.

Ellsberg died Friday morning at his home in Kensington, Calif., of pancreatic cancer, his family said. He was diagnosed in February and revealed the diagnosis on social media in March.

His family said he was in no pain and surrounded by loved ones when he died.

“Daniel was a truth-seeker and patriotic truth-teller, an anti-war activist, a beloved husband, father, grandfather and great-grandfather, a dear friend to many and an inspiration to many more,” said his family “He will be greatly missed by all of us.”

In a tribute on Twitter, his son Robert Ellsberg remembered as his father once said he would like his tombstone to say, “He became part of the anti-Vietnam and anti-nuclear movement.”

At one point he said, if he had a tombstone, it would say, “He became part of the anti-Vietnam and anti-nuclear movement.” Coincidentally, my interview about it was published today, for its release this Father’s Day weekend. https://t.co/NoxgQzSXov

— @RobertEllsberg (@RobertEllsberg) June 16, 2023

Until the early 1970s, when he revealed that he was the source of the stunning media reports on the Defense Department’s 47-volume, 7,000-page study of the U.S. role in Indochina, Ellsberg was a member well placed of the government and military elite. .

He was a Harvard graduate and self-described “cold warrior” who served as a private and government consultant in Vietnam during the 1960s, risked his life on the battlefield, received the highest security clearances and become trusted by Democratic and Republican officials. administrations

He was especially valued, he would later note, for his “talent for discretion.”

But like millions of other Americans, inside and outside the government, he had turned against the war for years in Vietnam, the government’s claims that the battle was winnable and that a North Vietnamese victory over the South supported by the United States would lead to the spread. of communism throughout the region. Unlike so many other opponents of the war, he was in a special position to make a difference.

“An entire generation of Vietnam-era insiders had become disillusioned like me with a war they saw as hopeless and endless,” he wrote in his 2002 memoir, “Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Documents of the Pentagon”. “By 1968, if not before, they all wanted, like me, to see us out of this war.”

Owen Franken/Getty Images

As much as anyone, Ellsberg embodied the conscientious individual, who responded only to his sense of right and wrong, even if the price was his own freedom. David Halberstam, the late author and Vietnam War correspondent who knew Ellsberg since they were both posted overseas, would describe him as a regular convert. He was highly intelligent, obsessively curious and deeply sensitive, a born proselytizer who “saw political events in terms of moral absolutes” and demanded consequences for abuses of power.

As much as anyone, Ellsberg also embodied the decline of American idealism in foreign policy in the 1960s and 1970s and the reversal of the post-World War II consensus that communism, real or suspected, had to be oppose the whole world.

The Pentagon Papers had been commissioned in 1967 by the then Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamaraa major public defender of the war who wanted to leave behind a comprehensive history of the US and Vietnam and help his successors avoid the kind of mistakes he would only admit much later.

The papers covered more than 20 years, from France’s failed colonization efforts in the 1940s and 1950s to the growing involvement of the US, including bombing and the deployment of hundreds of thousands of ground troops during the Lyndon Johnson administration . Ellsberg was among those asked to work on the study, focusing on 1961, when newly elected President John F. Kennedy began adding advisers and support units.

First published in The New York Times in June 1971, with The Washington Post, The Associated Press and more than a dozen others following, the classified papers documented that the US had defied a 1954 agreement without a military presence foreign investment in Vietnam, questioned whether South Vietnam had a viable government, had secretly expanded the war into neighboring countries, and had conspired to send American troops even though Johnson promised not to.

The Johnson administration had dramatically and covertly escalated the war despite the “judgment of the government’s intelligence community that the measures would not” weaken the North Vietnamese, wrote Neil Sheehan of the Times, a former correspondent in Vietnam who later wrote a Pulitzer Prize winning book. about the war, “A Bright Shining Lie.”

Bettmann

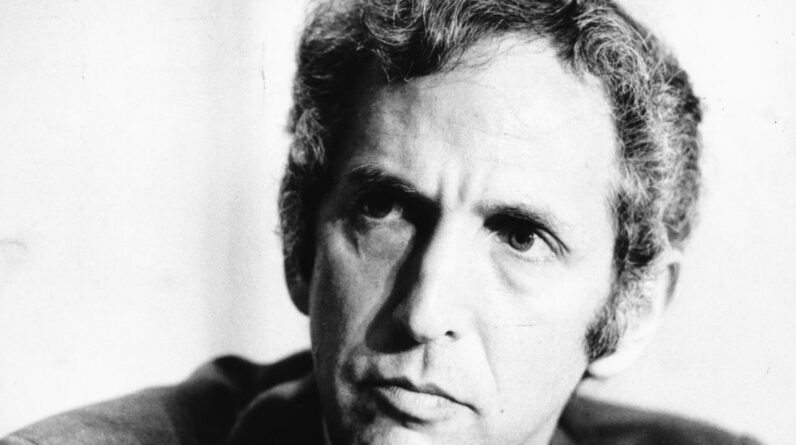

The leaker’s identity became a national guessing game, and Ellsberg proved an obvious suspect, given his access to the papers and his public condemnation of the war over the previous two years. With the FBI in hot pursuit, Ellsberg turned himself in to authorities in Boston, becoming a hero of the anti-war movement and a traitor to war supporters, labeled the “most dangerous man in America”. by national security adviser Henry Kissinger, with whom Ellsberg had once been friendly.

The papers themselves were seen by many as an indictment not just of a particular president or party, but of a generation of political leadership. Historian and philosopher Hannah Arendt would point out that the growing mistrust of the government during the Vietnam era, “the credibility gap,” had “opened into an abyss.”

“The quicksand of false statements of all kinds, deception and self-delusion, is apt to engulf any reader willing to investigate this material, which, unfortunately, he must recognize as the infrastructure of almost a decade of aliens and aliens from the States United. domestic politics,” he wrote.

The Nixon administration quickly tried to block further publication on the grounds that the papers would compromise national security, but the US Supreme Court ruled 6-3 in favor of the papers on June 30, 1971, a landmark ruling in the First Amendment that rejected prior restraint.

Nixon himself, initially unconcerned by the newspapers prior to his time in office, was determined to punish Ellsberg and formed a renegade team of White House “lightmen” equipped with a stash of House “hush money” Blanca and the mission to prevent future leaks.

“You can’t let it go,” Nixon told his chief of staff, HR Haldeman, privately. “You can’t let the Jew steal these things and walk away. Got it?”

Frank Wing/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Ellsberg faced trials in Boston and Los Angeles on federal charges of espionage and theft, with a possible sentence of more than 100 years. He had expected to go to prison, but was spared, in part, the wrath of Nixon and the excesses of those around him.

The Boston case ended in a mistrial because the government overheard conversations between a defense witness and his attorney. The charges in the Los Angeles trial were dismissed after Judge Matthew Byrne learned that White House “plumbers” G. Gordon Liddy and E. Howard Hunt had burglarized Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office in Beverly Hills , California.

Byrne ruled that “the strange facts have incurably infected the prosecution of this case.”

Meanwhile, the “Plumbers” continued their crime spree, notably the June 1972 attack on the Democratic Party’s national headquarters at the Watergate Hotel in Washington, DC. The Watergate scandal did not prevent Nixon from winning re-election in a landslide in 1972. but it would expand rapidly during his second term and culminate in his resignation in August 1974. US combat troops already they had left Vietnam and the North Vietnamese captured the South’s capital, Saigon, in April 1975.

“Without Nixon’s obsession with me, he would have stayed in office,” Ellsberg told The Associated Press in 1999. “And if he hadn’t been impeached, he would have continued the bombing (of Vietnam).”

Trending news

[ad_2]

Source link