Any reporter who has covered elected officials for a short period of time has likely heard this:

Why don’t you write stories about all the good things we’re doing?

Often, it comes from politicians who are under fire, for incompetence or worse. It’s usually desperation, an attempt to divert unwanted attention from bad news.

Some go so far as to spend tax money on spin doctors, to spread their good news. Or they make their own videos or newsletters to explain what their “achievements” are.

One of the purposes of this weekly column is to bring you insights into the newsroom, and this one examines one aspect of the relationships between journalists and some of the people they cover.

The best answer I can offer to the question of why we don’t write the good news about politicians comes from someone else. It’s an anecdote from my reporting days.

I was working with a reporting partner on a story about possible police jobs, which were under investigation at the behest of a mayor. My partner and I learned of a connection between the events and the police chief and were trying to uncover details. (Since this was so long ago, I’m not identifying the city, mayor or chief. No need to drag their names through the old mud.)

We were at our desks in the newsroom when Tomo, Tom O’Hara, then managing editor of The Plain Dealer, stopped by to ask why the police chief wanted to talk to him. We were not surprised. The boss wasn’t the first public official that crossed our minds, but it was a ploy that would never work with an old-school reporter like Tomo.

We explained what we were after and Tomo went to his office to return the boss’s call. He came back later and said we would meet with the station master. He said the boss wanted Tomo to be there when he talked to us.

When we arrived, however, the chief’s assistant came out to tell us that the chief wanted to speak to Tomo alone. Tomo refused, pointing out that he was just there to sit, that my partner and I were the ones doing the reporting.

The chief’s representative left to deliver this message, but soon returned to say that the chief insisted on an audience with Tomo alone. Tomo gave us a look that said, “Don’t worry. I got this,” and left us sitting stewing in the waiting area. After a while, we were ushered into a conference room with the boss, a another police officer and Tomo.

Tomo quickly took the floor. I didn’t take notes or record what he said, but it went something like this:

So here we are. My men are looking for details about your past relationships and any connection to a growing investigation. And you’re thinking they’re just looking for you for no reason.

The head nodded.

You think we’re being completely unfair because you’ve done nothing wrong to deserve this attention and shouldn’t have your reputation tarnished by a story.

The head nodded a little more noticeably, a smile starting on his face.

Besides, you’re thinking that you and your department are doing a great job, protecting the citizens and catching the bad guys. From where you sit, we are always reporting bad news about the department when we should be reporting good news about how your people go out every day to provide service to residents in heroic ways.

The way Tomo delivered the message, one would think that he really agreed with the boss’s perspective, and the boss was excitedly sitting forward and nodding vigorously.

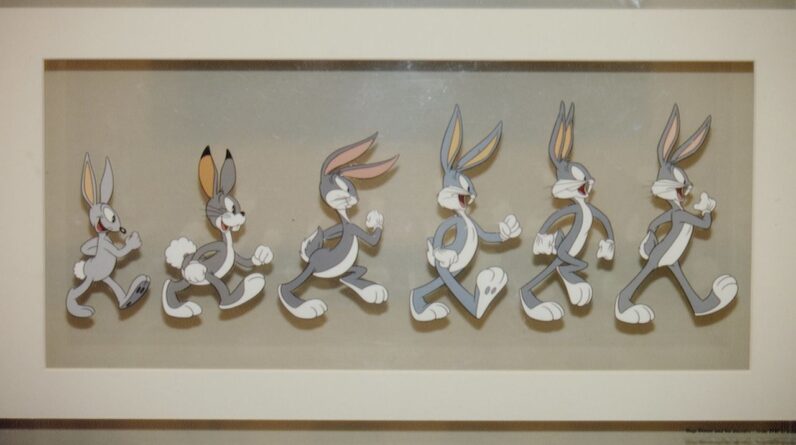

I’m stopping here to give you an exact idea of how this went, and the best way to illustrate the drawn head reaction is a cartoon: Bugs Bunny. In 1950, the Looney Tunes people produced a Bugs Bunny short called The Rabbit of Seville, almost entirely set to music from the opening to the Barber of Seville, an opera by Gioachino Rossini.

The short is full of typical slapstick mayhem with Bugs and Elmer Fudd, but the scene I notice has Elmer in a barber chair while Bugs massages his scalp with hair tonic and something called Figaro Fertilizer . The massage over, Bugs holds up a mirror and Elmer gets more and more ecstatic, as does the Chief of Police, while what appears to be hair grows on his bald head. And then the hair sprouts flowers, crushing Elmer’s rapture and restarting the chaos. You can watch the scene at

The police chief was having the same moment of elation that Tomo was talking about. He clearly thought he had won over our Editor-in-Chief. And then it was time for the boss to bloom.

Well, guess what: it’s not news that you do your job. That’s what taxpayers pay you for. You are supposed to serve the citizens and keep them safe. Doing what you’re supposed to do is not news. The news is what’s interesting. These are things that are not supposed to happen. And if these reporters get information that something isn’t right, it’s their job to find out and write about it. That’s what they get paid for.

His head was crushed, he fell back in his chair and lost his smile. Tomo continued for a while. We suspected he laid it thick for our benefit; knowing how annoying we were in the waiting room. His point, however, was delivered superbly.

I wasn’t saying we don’t write human interest stories about people doing good work. Nor was he saying that all the news we report is bad. His message was that the news is what is interesting and unexpected. We don’t write stories to say the mail was delivered today. Or the trash was picked up. Or that grass was cut. It’s not interesting.

And for those politicians who ask why we don’t write about all the good things they are doing, the truth is we do. If an elected leader launches a new program to solve a problem, we write about it. We get stories like that all the time.

Yet skillful successful politicians generally don’t ask why we don’t write about the good things they’re doing. It is bad leaders who ask the question. Somehow they forget that they sought their jobs, asking you to vote for them, to do public service, but have come to see themselves as victims of the petty media.

Journalists quickly learn that when leaders resort to the pathetic question, their days in leadership are likely to be numbered and journalists can start thinking about their replacements. Or, to quote Bugs after sending Elmer to the Rabbit of Seville, “NEXT!”

I’m at cquinn@cleveland.com

Thanks for reading.

[ad_2]

Source link