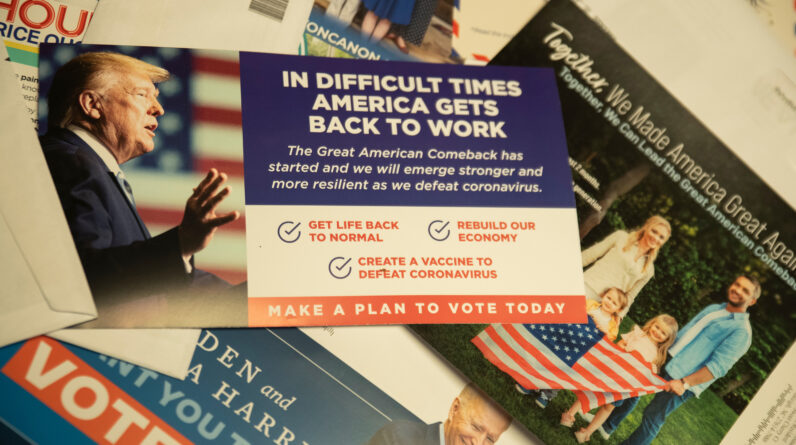

The recent US election has raised the question of whether “microtargeting”, the use of extensive online data to tailor persuasive messages to voters, has altered the political playing field.

Now, a newly published study led by MIT scholars finds that while targeting is effective in some policy contexts, the “micro” side of things may not be the game-changing tool that some have assumed.

“In a traditional messaging context where you have an issue you’re trying to convince people of, we found that targeting had a substantial persuasive advantage,” says David Rand, an MIT professor and co-author of the study.

In fact, the study found that tailoring political ads based on an attribute of your target audience, such as party affiliation, can be 70 percent more effective at influencing support for the policy than simply showing everyone the single ad that is expected to be most persuasive worldwide. population But targeting political ads with multiple attributes (eg, ideology, age, and moral values) added no additional benefit to the study.

“We haven’t found much evidence that microtargeting works,” says Rand, who is the Erwin H. Schell Professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management. “We found that we had as much persuasive advantage from single-attribute targeting as from multi-attribute targeting.”

The paper, “Quantifying the potential persuasive returns of political microtargeting”, is published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The authors are Ben Tappin, a postdoc at the University of London and an affiliated researcher with the MIT Applied Cooperation Team; Chloe Wittenberg, PhD candidate in MIT’s Department of Political Science; Luke Hewitt PhD ’22, visiting researcher at the Stanford Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society; Adam Berinsky, the Mitsui Professor of Political Science at MIT; and Rand, who is also a professor of brain and cognitive science at MIT and director of the Applied Cooperation Team.

Road test messages

Political microtargeting became the subject of widespread attention after the 2016 US election, when it became widely known that the firm Cambridge Analytica had used Facebook data to craft highly targeted messages to voters. What scholars have found less clear since then is: Did these ads work?

To assess this question, the researchers conducted sets of survey experiments in 2022, using the online survey platform Lucid. In the first phase, with more than 23,000 participants, the researchers created ads for two issue-based campaigns: one focused on the US Citizenship Act of 2021 and the second focused on Universal Basic Income. Participants were randomly divided into a control group, which received only basic information about the relevant policy, or into several different treatment groups, each of which saw a video ad intended to influence opinions about that policy. This approach parallels the actual campaign practice of testing many ad types and then seeing which one is most effective.

In the second phase of the study, the researchers simulated multiple campaign strategies. More than 5,000 participants were reassigned to a control group, which received the same basic problem information as in the first phase, or to one of three treatment groups. Members of these treatment groups saw the best-performing message from the first phase of the study; a randomly selected ad; or a “targeted” ad selected from a machine learning model trained on data from the first phase of the study. To assess the added benefit of microtargeting, the researchers also varied the complexity of the targeting process used to match ads to participants, targeting those participants using between one and four personal characteristics.

Using this multistage design, the researchers were able to evaluate the effectiveness of a targeting strategy against many other widely used campaign advertising tactics.

Ultimately, the targeting strategy performed better than these other tactics, but microtargeted ads based on multiple voter characteristics were no more effective than those based on a single characteristic.

The researchers hope their findings will help inform ongoing debates about microtargeting and political campaigns in the United States.

“There has been a lot of speculation about the promises and dangers of microtargeting for the functioning of our democratic system,” says Berinsky. “Our study allows us to rigorously assess the potential impact of political microtargeting in the real world.”

One ad does not fit all

Rand emphasizes that the study’s results occupy a middle ground; Microtargeting is probably not the seemingly overwhelming force that people fear it to be, but targeted political ads still have an edge most of the time.

“In terms of the implications for political advertising, it certainly seems like targeting is often going to be a good idea, and if you don’t, you might be leaving persuasive power on the table,” says Rand. “At the same time, it’s clearly not mind control.”

It’s important to remember that microtargeting in the context of political persuasion works differently than it does for business advertising, Rand suggests, because it’s difficult to generate the data needed to train political targeting models and distribute ads resulting

Microtargeting in politics also works differently than in business advertising, Rand suggests, because it’s difficult to generate the data needed to train political targeting models and distribute the resulting ads.

“If Facebook is doing microtargeting based on the sale of widgets, it can get good feedback on whether or not you bought the widgets, and then use that data to continually optimize targeting,” says Rand. In politics, it is much more difficult to obtain reliable information about voter attitudes and voting decisions, making effective microtargeting of political ads at scale very difficult.

While their results suggest that political ad targeting can be effective in some contexts, the researchers also note several reasons why targeting may work differently, and perhaps less effectively, outside of the experimental context that they developed. On the one hand, the benefits of microtargeting varied substantially between the two main policies under study. These benefits were even smaller in the second experiment, which focused on an alternative, albeit less common, campaign situation.

As Wittenberg suggests, “it’s important to understand not only if microtargeting is effective, but also when.”

Other work by Rand and Berinsky has been funded by Google and Meta.

[ad_2]

Source link