Last Saturday, dozens of former aides, friends, supporters and dignitaries gathered at the former synagogue that houses the headquarters of the Rainbow PUSH Coalition on Chicago’s South Side to commemorate the Rev. Jesse Jackson’s second presidential campaign 35 years ago. The organization’s founder, once a six-foot-plus, broad-shouldered college football star, is now led by a group of trusted aides. Parkinson’s disease has ravaged the body of Mr. Jackson and has stopped his speech, although according to those around him, it has not slowed his mind.

Fifty-two years ago, at the age of 30, Mr. Jackson broke away from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which had been led by the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. before his death, to form his own organization, Operation PUSH. , which was first People United to Save Humanity and later People United to Serve Humanity (and later merged with the Rainbow Coalition). Mr. Jackson, now 81, announced that he would transfer day-to-day leadership of the organization to the Rev. Dr. Frederick Haynes III, a 62-year-old pastor from Texas.

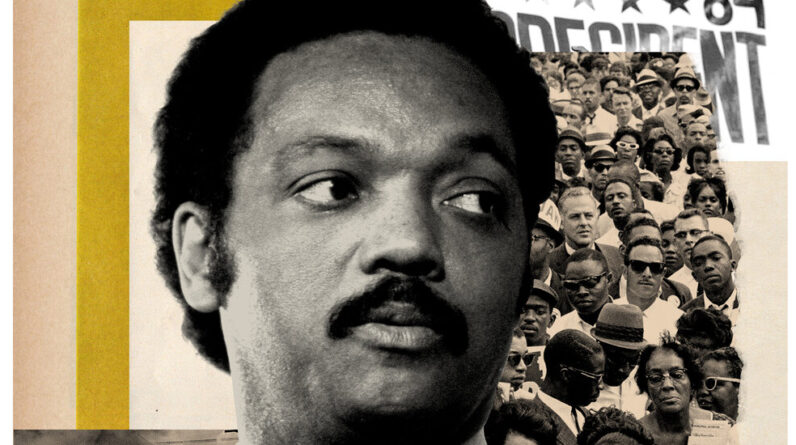

39 years have passed since Mr. Jackson was running for office for the first time, and yet what he represents: a living link to the civil rights movement and a symbol of the work that remains to fulfill that movement’s dream of full equality for blacks in the United States. —it’s a beautiful thing. Perhaps even more considering that Mr. Jackson remains a complicated and misunderstood figure, whose work is as misunderstood as it is seemingly ubiquitous.

Mr. Jackson left the seminary to go with Dr. King in Selma, Alabama, and finally entering the inner circle. It was there the day Dr. King was killed, wearing a shirt he said was stained with the blood of Dr. King. From that point on, he would use his extraordinary oratory skills and ability to attract media attention to become one of the best-known blacks in America and perhaps the world.

Dr. King had sent Mr. Jackson to Chicago in 1966 to manage Operation Breadbasket. He had a bold mission: to address the economic conditions of black people. Tasked with moving the movement beyond droughts and protests aimed at securing basic decency for southern blacks, Breadbasket addressed poor housing conditions, persistent de facto and de jure racial exclusion, and the diversity of products that stocked store shelves in minority. communities

Mr. Jackson learned and expanded on the tactics pioneered by Dr. King. In 1966, Dr. King and his wife, Coretta, lived briefly in a dilapidated housing project in Chicago to highlight the landlords’ treatment of poor blacks, prompting the city to crack down on substandard living conditions. Months later, the threat of peaceful marches through the white Chicago suburb of Cicero drew the ire of the American Nazi Party, which attempted to form a counter-protest. The march was called off after Dr. King reached an agreement with Chicago leaders to open more housing in the city to blacks. President Lyndon Johnson seized on the momentum of national mourning following the assassination of Dr. King to push Congress to pass the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

In the years following the assassination of Dr. King, boycotts of Operation Breadbasket and local business pickets of Mr. Jackson became legendary. Later, the organization’s ambitions grew, and after the breakup of Mr. Jackson with SCLC, began targeting more powerful interests, moving into national companies such as Pepsico and the A&P grocery store. A similar pattern played out in dozens of meetings with countless corporate entities over decades. There were times when the mere threat of a meeting with Mr. Jackson set off a cascade of events that led to new opportunities for black business owners looking to buy franchises and executives who were locked out of board positions and management positions. At other times, seeking to avoid the heat, corporations moved proactively to diversify their boards or corporate ranks.

Mr. Jackson often said he considered himself a “tree shaker, not a jello maker.” Those who worked for him knew the saying well: After all, they were the ones in charge of picking the fruit from the ground to make the jelly.

Could anyone else shake the tree like Jesse Jackson? And even if they could, would America still value it? At a time when diversity is again under political attack, the tactics that Mr. Jackson was a trailblazer, and the doors of opportunity she opened for countless women and people of color in corporate America are also under attack.

Almost immediately after the death of Dr. King, Mr. Jackson moved to fill the void left in the civil rights movement. But it wasn’t until more than a decade later that he started looking at politics. The efforts of Mr. Jackson to register voters in Chicago helped propel Harold Washington into office in 1983, making him the city’s first black mayor. Mr. Jackson criss-crossed the country to register voters, especially in the South. It would eventually fuel his unlikely national candidacy for the presidency. Despite years of living in Chicago, he never lost his South Carolina accent or his connection to a network of southern black churches that sustained his ministry and activism. Mr. Jackson never pastored a congregation, but ministered to an itinerant flock, preaching the virtues of civic engagement. His parable of unregistered voters (especially in the South) as pebbles in David’s sling in his fight against Goliath became a cornerstone of his presidential campaigns.

The political influence of Mr. Jackson felt most acutely on the left, which has been shaped by the ideas he pursued in his presidential campaigns, his emphasis on increasing the electorate through widespread voter registration of young people and people of color, and for the dozens of people who at some point made their way through its orbit. Among them: Cabinet members like former Labor Secretary Alexis Herman, Rep. Maxine Waters, political strategist Donna Brazile and Housing and Urban Development Secretary Marcia Fudge.

Many Americans, especially black Americans, remember the spectacle of Mr. Jackson: The mass demonstrations, the chants of “Run, Jesse, run!” But these campaigns also fused a unique platform of economic populism, social justice, and moral urgency. Although Mr. Jackson successfully mobilized and energized black voters, his candidacy is better remembered for mobilizing voters not on race but on moral imperatives and political prescriptions than the current Democratic Party. look forward

The shorthand of the historic candidacies of Mr. Jackson in the 1980s correctly labels him as the most serious black candidate for the presidency until Barack Obama emerged two decades later. But the greatest success of Mr. Jackson was not, as some thought, his race, but the political platform he built. In 1984 and 1988, he ran to end economic inequality, introduce universal health care, and promote America first policies that would reverberate for decades to come. He envisioned a coalition of black, white, Asian, Native, rural, urban, gay, and straight people coming together to achieve social justice as much as economic justice.

“When we form a great quilt of unity and common ground, we will have the power to bring health care, housing, jobs and education and hope to our nation,” said Mr. . Jackson. his speech at the 1988 Democratic Convention. His unsuccessful campaigns had a concrete consequence: Mr. Jackson negotiated permanent changes to the Democratic Party’s nominating process, including the end of its winner-take-all primary system, which made possible Barack Obama’s first victory in the Democratic primary. At the time of the candidacy of Mr. Obama in office, an entire generation of black Americans had seen and expected a black man in the White House. “We raised the low ceiling,” mused Mr. Jackson. “We raised the roof with the possibility of Black.”

Abby D. Phillip is senior political correspondent and host of “Inside Politics” on CNN. He is writing a book about Jesse Jackson’s legacy in American politics.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d love to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here it is advices. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow the New York Times opinion section Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) i Instagram.

[ad_2]

Source link