It is estimated that the planet is covered with about 400 million tons plastic waste every year that will not break over time. But this week, scientists said they may have found a way to help, thanks to tiny organisms in one of the coldest regions on Earth.

Researchers from the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research WSL recently uncovered Arctic and Alpine microbes that could be the key to eliminating some forms of plastic waste. Microbes, they found, will eat certain types of plastic left in their environment, a discovery that could help pave the way for reducing much of the plastic waste found on the planet.

Using microorganisms to eat plastic is not a new concept, but industries have relied on microbes that require temperatures of at least 86 degrees Fahrenheit to carry out their feast. This requirement makes the recycling process more energy and financially intensive.

But the newly discovered microbes were found to break down plastics at temperatures as low as 59 degrees Fahrenheit, which if scaled up in industry could, in theory, make the process more efficient.

Joel Rüthi

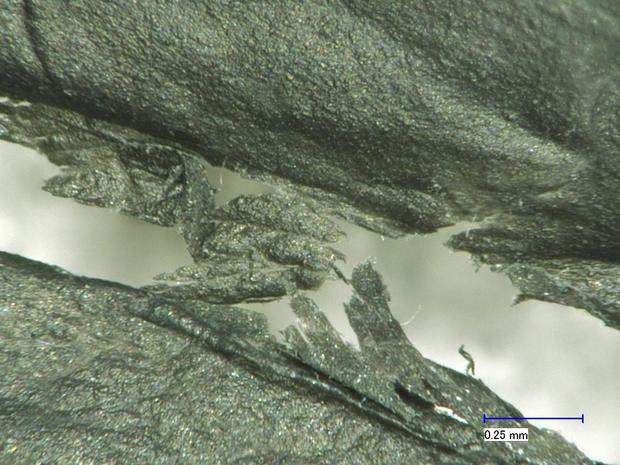

This discovery was made after researchers buried pieces of plastic in the soil of Greenland and the Alps. In the following months, they observed bacteria and fungi growing on plastic. A year after planting the pieces of plastic, they took the microbes found there and conducted further tests in controlled environments in a laboratory to determine how many types of plastic they could consume.

Of the 34 cold-adapted microbes they studied, they found that 19 of the strains secreted enzymes that could break down some plastics. However, the only plastics that could be broken down were those that were biodegradable: none of the microbes could break down more traditional plastics, made of polyethylene plastic.

Their findings were published in Frontiers in microbiology on Wednesday, just months after the team published complementary research that found polyethylene plastics, often used in trash bags, don’t break over time, and that even the biodegradable plastics used in composting bags take an exceptionally long time to break down.

And while the discovery could be a key to paving the way to a better future for plastics recycling, scientists say there’s still a lot of work to be done.

“The next big challenge will be to identify the plastic-degrading enzymes produced by microbes and to optimize the process to obtain large amounts of enzymes,” said study co-author Beat Frey. “Furthermore, further modification of the enzymes might be necessary to optimize properties such as their stability.”

Protecting the planet: news and features on climate change

More More Lee Cohen

[ad_2]

Source link