Why wait for the morning edition when you can write the news in the light?

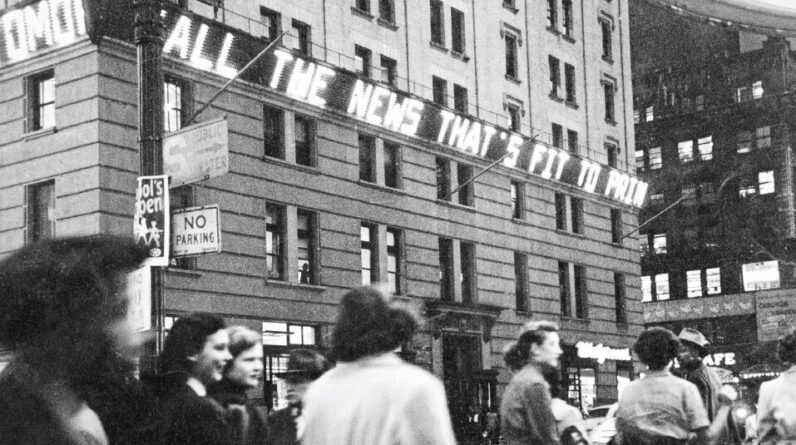

In the early 20th century, newspapers struggled to find faster ways than print to relay breaking news, especially on presidential election nights. None was as famous as the New York Times Motograph, an electric billboard 368 feet long. Better known as “zipper”, came to life on November 6, 1928to inform the crowd in Times Square that Herbert Hoover had defeated Governor Alfred E. Smith of New York.

Five-foot-tall words made up of 14,800 light bulbs moved endlessly around the sign, wrapped like a ribbon above the third floor of the slender Times Tower on West 42nd Street.

Behind the sign was a control room where operators assembled words from individual 7½-inch-long Bakelite plastic plates, each with a letter made of Monel, a nickel-copper alloy. Collected by a conveyor chain, the plates would pass under thousands of metal brushes. Whenever the brushes touched the Monel letters, an electric current briefly flowed to the corresponding light bulbs on the outside of the tower, creating the illusion of movement.

“The device is not only an electrical signal, but in a sense it is also a newspaper,” wrote The Times on November 8, 1928, another way of saying that the publisher and editors were “platform agnostic,” wedded to no single technology for delivering the news.

At 7:03 p.m. on August 14, 1945, moments after President Harry S. Truman spoke at the White House, the zipper lit up. “OFFICIAL — TRUMAN ANNOUNCES THE JAPANESE SURRENDER” he told the jubilant, giddy crowd.

After The Times sold Times Tower in 1961, the sign was rebuilt and sponsored in turn by Life magazine, Newsday and Dow Jones & Company, which dismantled the bulb assembly in 1997 and replaced it with a digital zipper . A Bakelite “S” plaque is on display today at The Times Museum.

The In Times Past column explores the history of the New York Times through artifacts.

[ad_2]

Source link