CNN

—

Almost 62,000 people died from the heat last year during Europe’s hottest summer on record, a new study has found – more heartbreaking evidence that heat is a silent killer and its victims are very underestimated

The study, published on Monday in journal Nature Medicine, found that 61,672 died in Europe from heat-related illnesses between May 30 and September 4 last year. Italy was the most affected country, with around 18,000 dead, followed by Spain with just over 11,000 and Germany with around 8,000.

The researchers also found that extreme heat disproportionately harmed older people and women. Of the nearly 62,000 deaths analyzed, the heat-related death rate was 63% higher in women than in men. Age was also an important factor, with the The number of deaths increases significantly among people aged 65 and over.

“It’s a very large number,” Joan Ballester, an ISGlobal epidemiologist and lead author of the study, told CNN.

Eurostat, which is Europe’s statistics office, tried to quantify the number of heatwave deaths last year by counting excess deaths, or how many people died more than in a normal summer. But Ballester, who lives in Spain and sweated out last year’s heat wave, said the study released Monday was the first to look at how many deaths last summer were caused specifically by the heat.

The researchers analyzed temperature and mortality data between 2015 and 2022 from 35 European countries, representing a total population of 543 million people, and used them to create epidemiological models to calculate heat-related deaths.

“For me, I’m an epidemiologist, so I know what to expect and (the death toll) is not surprising, but for the general population, this is very likely to be surprising,” he said.

The region has seen this scenario before: An unprecedented heat wave led to more than 70,000 excess deaths in the summer of 2003. This heat wave was an “exceptionally rare event,” the study’s scientists said , even when human-caused climate is taken into account. crisis

The 2003 heat wave was a wake-up call, the researchers said. It showed that Europe at the time lacked the kind of preparedness to avoid a mass-casualty heat event and exposed the fragile nature of the region’s health system, Ballester said, especially as weather extremes become more frequent. frequent and intense.

But the study’s findings show that even Europe’s current prevention plans are still not enough to keep up with the breakneck pace at which dangerous heatwaves are occurring and claiming even more lives at risk

“The fact that more than 61,600 people in Europe died from heat stress in the summer of 2022, even though, unlike in 2003, many countries already had active prevention plans, suggests that currently available adaptation strategies can still be insufficient,” he said. Hicham Achebak, co-author of the study and ISGlobal researcher.

While the numbers could have been worse without the region’s current heat prevention plans, the authors warn that the world will only get warmer, and that without effective adaptation plans, Europe could face more than 68,000 premature deaths each summer by 2030. and more than 94,000 by 2040.

“The acceleration of warming observed over the past 10 years underscores the urgent need to substantially reassess and strengthen prevention plans,” Achebak said.

Monday’s study shows just how serious a health risk extreme heat can be. In the US, heat kills more Americans than any other weather-related disaster, and the climate crisis has made these extreme events more deadly. Heat deaths have outnumbered hurricane deaths in the country by more than 8 to 1 over the past decade, according to tracked data by the National Meteorological Service.

However, US heat death numbers would suggest that far fewer people die from heat than in Europe. In accordance with data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 700 people die each year from the heat.

David S. Jones, a physician and historian at Harvard University, said there are a couple of explanations for why the U.S. statistics seem low: The U.S. could be underestimating its numbers, or the heat is deadlier in Europe due to the lack of air conditioning. or it could be a combination of the two.

Jones, who is not involved in Monday’s study, said only 5 percent of homes in France have air conditioning, for example, compared to almost 90% in the USA

“There is also reason to believe that places that are more often exposed to heat, like the American South, are actually less vulnerable to heat than places like the northeastern United States or Chicago or Europe.” , Jones said.

“But it goes back to this question of, well, does Europe just report more accurately than the US?” he said “There have been people who have been frustrated with the quality of US health data across the board, not just heat, but everything else, for decades.”

John Balbus, the acting director of the US Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Climate Change and Health Equity, said the number is lower because the CDC only counts people whose death certificates indicate specifically that heat was the cause of death, rather than a contributing factor.

A study 2020 found that heat-related deaths were being underestimated in 297 of the nation’s most populous counties. The researchers said death records tend to neglect other potentially heat-related causes of death, such as heart attacks.

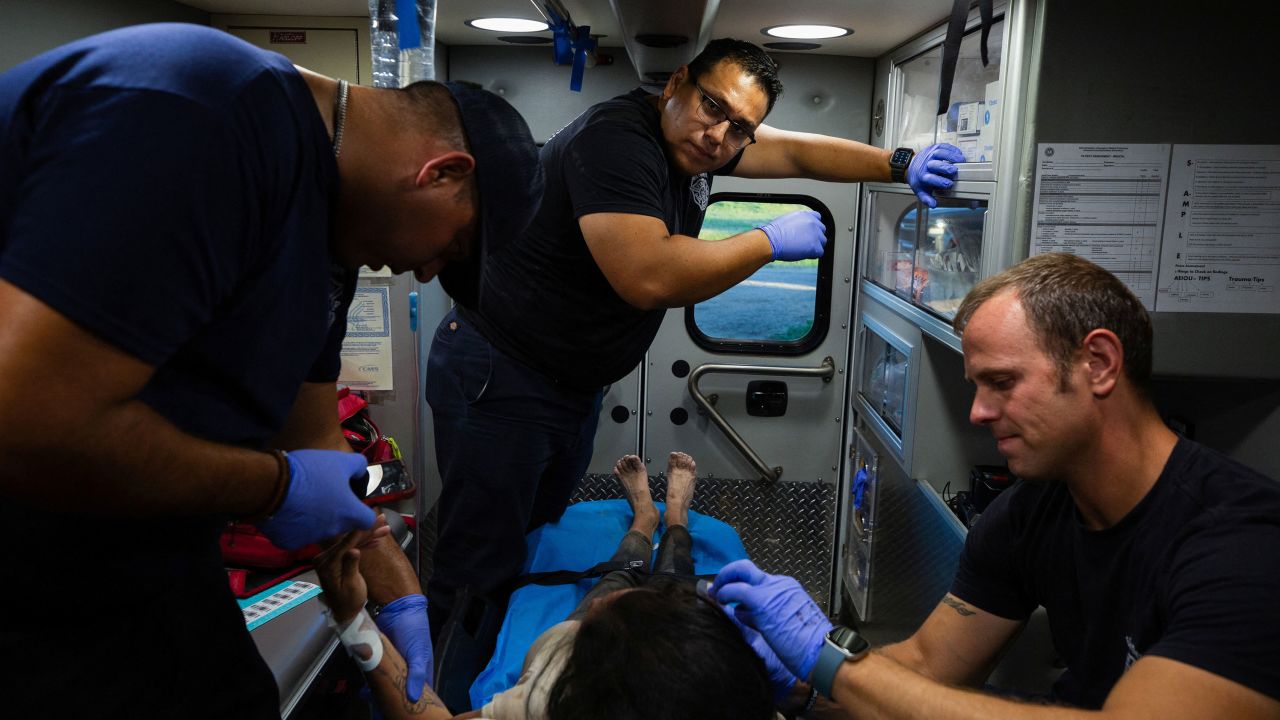

But there are other ways to know how many people in the US are being harmed by increasingly frequent heat waves. Balbus noted that the CDC tracks the number of people who present to emergency rooms for heat-related illnesses.

The Biden administration is working on short-term solutions to the heat, Balbus said, such as more effective counseling and putting air conditioners in the hands of low-income families.

But they also have an eye on the long term through recent legislation: planting more trees and green spaces in urban areas, which cools the surrounding air; provide support to communities for reflective streets and roofs; and working to modernize building codes so they trap less heat.

Still, Balbus said, as temperatures continue to rise, more funding should be devoted to studying and tracking the health impacts of the climate crisis.

“We’re doing the best we can with the resources we have,” Balbus said. “And we could do more with more capacity, but it’s something that has scientific challenges and requires support.”

[ad_2]

Source link