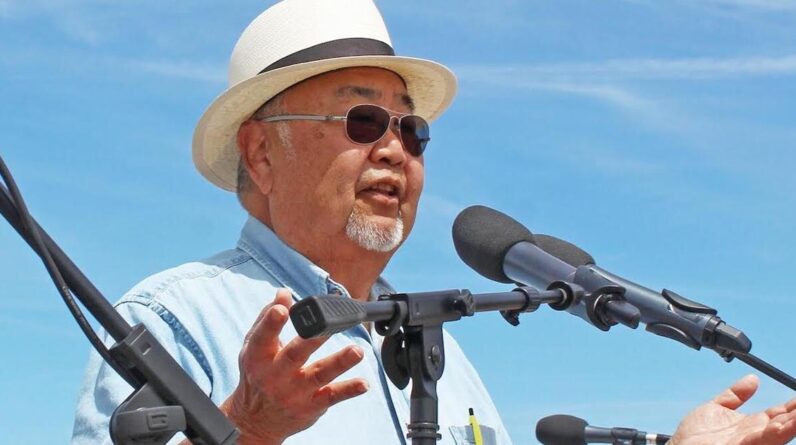

Warren Furutani knows this season of his life is about his legacy.

The community activist and politician who served in the state assembly and on school boards for 30 years has a long way to go. In his office in the Harbor Gateway area of Los Angeles, Furutani is softer than when he served as the no-nonsense assemblyman representing the 55th district.

“He was known for being straightforward, honest and straightforward in his interactions with others,” said Councilman Kevin De León, a former assemblyman colleague. “And to not be afraid to say what he thinks or defend what he believed.”

At 75 years old and retired from politics, Furutani has embraced a new title: grandfather.

“It’s great,” Furutani said.

No meetings or budgets to sweat. There’s time to catch up with the neighbors and room to build a tree house for your granddaughter. During the first days of pandemic isolation, he retreated daily to his office with iced coffee to record his legacy in his memoir, “Activ-ist.”

The narrative of Furutani’s book and career is rooted in Los Angeles and stretches from Little Tokyo to the state Capitol and beyond. It’s a love song for the city and the communities it served. From political rallies to community organizations in the shadow of Los Angeles City Hall, Furutani was there with his booming voice and uncanny ability to speak to the heart of a cause.

“I saw Warren as a visionary and revolutionary thinker,” said Nobuko Miyamoto, artist and director of Great Leap, a multicultural arts program based in Los Angeles.

His vision has always been the same: to bring about political or social change.

‘Ac-tiv-is’

During his 1984 presidential bid, Jesse Jackson became the first presidential candidate to make a campaign stop in Little Tokyo. The rallying point was in the courtyard of the Japanese American Community and Cultural Center with its red hardscape designed by Isamu Noguchi. Furutani took the microphone, hushed the excited audience, and introduced Jackson.

Miyamoto was in the crowd, transfixed by Furutani’s words.

“Warren had this strange way of being himself and yet he had the same kind of charisma and a dynamic way of talking to people, for people and with people,” she said.

His feet were in Little Tokyo, but his vision was to create common ground with other communities. In 2020, Furutani came out of retirement from political life to work as a senior advisor to De León, primarily consulting on Little Tokyo issues.

It was the right choice, said Bill Watanabe, founding executive director of Little Tokyo Service Center.

“Warren has a long and deep connection to the Japanese American community, which is perhaps symbolized by his strong affinity for Little Tokyo,” Watanabe said.

After two years, Furutani quietly stepped down as an adviser, he said, a week before an audio recording of a conversation between several Los Angeles advisers filled with racist and derogatory remarks was leaked. De León was caught up in the controversy.

“I didn’t want anyone to think I left Kevin’s office because of political issues,” Furutani said. “My advice to Kevin was to weather the storm. Take it right on the chin, you know, mea culpa, and move on, because I think he really has a lot to bring to Los Angeles.”

This seems surprising from Furutani, who in 2011 nearly came to blows with another assemblyman over racially charged comments about Italian Americans. These incidents are different, he said, because one was done publicly on the floor of the assembly. The leaked audio tape appeared to be a secret recording of a private conversation.

Furthermore, Furutani would prefer to move away for the long-range vision of the city he loves.

A modest proposal

Furutani is no stranger to difficult jobs. Before serving two terms in the state assembly, he made history in 1987 as the first Asian Pacific Islander to be elected to the Los Angeles Unified School District Board. Of all his elected or appointed political positions, he said serving on the LAUSD school board was the most challenging job he’s ever held. That’s a bold statement, but it’s also not surprising given the size of the school district (the second largest in the United States) and the high stakes of making decisions that directly affect the most important member of any family.

From 1987 to 1995, Furutani was one of seven board members who oversaw changes to year-round school schedules and the launch of some of the state’s first charter schools.

Even though it’s legacy time, Furutani’s voice drips with passion when he talks about his ideas for solving some of the current issues plaguing the school district. He explains the plan in his book: a modest proposal for anyone willing to listen.

“Public education to me is the most important democratic institution in our country,” he said. “As the public education system goes, so goes our democracy.”

In “Ac-tiv-ist,” Furutani devotes a chapter to the pitfalls of public education as a “political battleground” mired in bureaucracy. When he first ran for school board, his son, Sei Malik Furutani, was entering kindergarten, so he had an interest. Prior to that, Furutani attended LAUSD schools as did his siblings and father. As he sees it, his family has a long-standing investment in the Los Angeles public education system.

And he sees systemic flaws.

It’s the only sentence in Furutani’s memoir that is printed in bold: He believes the crux of the problem is that LAUSD is too big. Managing it is like trying to steer an ocean liner. Because of its size, changing direction is difficult. As it stands, the school board makes decisions but only has authority over the superintendent, so the district’s large bureaucracy makes it inefficient and reactionary to problems.

Why not make LAUSD more nimble, he proposed, by dividing it into a federation of seven geographically divided school districts with seven elected school boards?

“I think it would encourage healthy competition between the different districts,” Furutani said. “But most importantly, it would facilitate participation at the local level.”

Education for all

Furutani was a school board member during a tumultuous time of painful budget cuts and overcrowding, said Jackie Goldberg, a current LAUSD school board member who served a stint with Furutani.

“I remember he and I would sometimes sit down at the end of a meeting and just cry,” Goldberg said.

During his tenure on the school board, LAUSD established the first 10 charter schools in California. The intent was to use charter schools as avenues for innovation and create different approaches to public education. But as it turned out, he said, charter schools have now become a workhorse for the privatization of public education.

“Instead of being a complement to the public education system, they are seen as competitors,” Furutani said. “The very basis of public education is that it is for everyone. A lot of the charter schools are doing a good job, I understand. But they are small. How does this play out in a large system?”

Politics and public service can be fickle. Once you leave the spotlight, it’s easy to forget, Furutani said. He paused there as if to let the words sink in. Can someone who spent most of their career agitating for change be okay with the stillness of retired life? Now, with his legacy recorded in his memoirs, he hesitated to punctuate his political career with a final mark. Instead, he appeared to leave the door open for a second non-retirement, a possibility his wife, Lisa Furutani, said is likely.

Perhaps there will be another appointed position in his future. After all, he served in the assembly with current Mayor Karen Bass.

“I want to help in any way I can,” Furutani said.

[ad_2]

Source link