W. Larry Kenney is a professor of physiology, kinesiology and human performance at Penn State; Daniel Vecellio is a geographer-climatologist and a postdoctoral fellow Penn State; Rachel Cottle is a Ph.D. candidate in exercise physiology a Penn State; i S. Toni Wolf is a postdoctoral researcher in kinesiology a Penn State.

The extreme heat has been breaking records all over EuropeAsia and North Americawith millions of people sweltering in far above “normal” heat and humidity for days on end.

Death Valley reaches a temperature of 128 degrees Fahrenheit (53.3 degrees Celsius) on July 16 – not the world’s hottest day on record, but close. Phoenix hit a record heat streak with 19 straight days of temperatures above 110 F (43.3 C), accompanied by a long streak of nights that never dropped below 90 F (32.2 C), leaving little chance to people without air conditioning to cool off. Globally, Earth probably had one hottest week on modern record at the beginning of July.

Heat waves are getting to overfeed as the weather changes: it lasts longer, becomes more frequent and hotter.

A question many people ask is, “When will it become too hot for normal daily activity as we know it, even for young, healthy adults?”

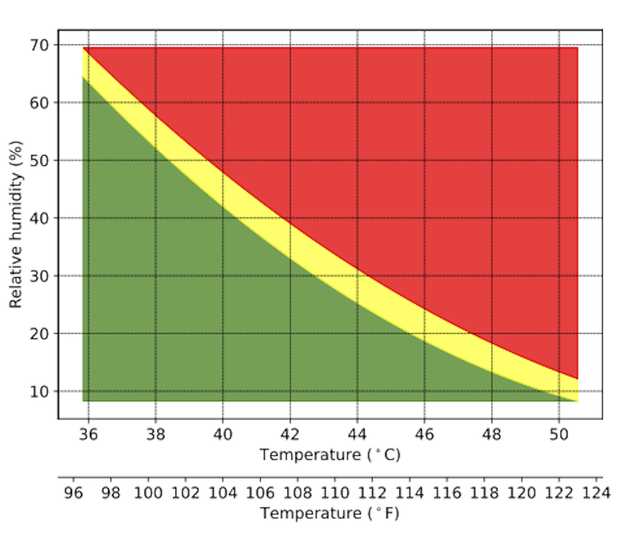

The answer goes beyond the temperature you see on the thermometer. It’s also about humidity. Our research is designed to reach the combination of the two, measured as “wet bulb temperature”. Together, heat and humidity put people at much greater risk, and the combination becomes dangerous at lower levels than scientists previously believed.

The limits of human adaptability

Scientists and other observers have been alarmed by the increasing frequency of extreme heat combined with high humidity.

In the Middle East, Asaluyeh, Iran, recorded an extremely dangerous situation maximum wet bulb temperature of 92.7 F (33.7 C). July 16, 2023 – above our measured upper limit of human adaptability to humid heat. India and Pakistan have also come close.

People often point to study published in 2010 who theorized that a wet-bulb temperature of 95 F (35 C), equal to a temperature of 95 F at 100% humidity, or 115 F at 50% humidity, would be the upper limit of safety, plus beyond which the human body can no longer cool itself by evaporating sweat from the body’s surface to maintain a stable body temperature.

It was not until recently that this limit was tested in humans in laboratory settings. The results of these tests show even greater cause for concern.

The PSU HEAT project

To answer the question of “How hot is too hot?” we brought healthy young men and women to the Noll Laboratory at Penn State University to experience heat stress in a controlled environmental chamber.

These experiments provide insight into what combinations of temperature and humidity begin to be harmful to even the healthiest of humans.

Patrick Mansell/Penn State

Each participant swallowed a small one telemetry tablet who continuously monitored their deep or core body temperature. They then sat in an environmental chamber, moving just enough to simulate the minimal activities of daily living, such as showering, cooking and eating. The researchers slowly increased the temperature in the chamber or the humidity in hundreds of separate experiments and monitored when the subject’s core temperature began to rise.

This combination of temperature and humidity at which the person’s core temperature begins to rise continuously is called “critical environmental limit.”

Below these limits, the body is able to maintain a relatively stable core temperature for long periods of time. Above these limits, the core temperature increases continuously and the risk of heat related illnesses with prolonged exposures increases.

When the body overheats, the heart has to work harder to pump blood flow to the skin to dissipate the heat, and when you’re also sweating, this decreases body fluids. In the most severe case, it can lead to prolonged exposure heatstrokea life-threatening problem that requires immediate and rapid cooling and medical treatment.

Our studies of healthy young men and women show that this upper environmental limit is even lower than the theorized 35 C. It occurs at a wet bulb temperature of about 87 F (31 C) in a range of environments above 50% relative humidity. This would be equivalent to 87 F at 100% humidity or 100 F (38 C) at 60% humidity.

W. Larry Kenney

Dry environments vs. wet

Current heat waves around the world are exceeding these critical environmental limits and approaching, if not exceeding, even theoretical wet-bulb limits of 95 F (35 C).

In hot, dry environments, critical environmental boundaries are not defined by wet-bulb temperatures, because almost all of the sweat produced by the body evaporates, which cools the body. However, the amount we humans can sweat is limited and we also get more heat from higher air temperatures.

Note that these cuts are based solely on preventing your body temperature from rising excessively. Even lower temperatures and humidity can put stress on the heart and other body systems.

A recent paper from our lab demonstrated this heart rate begins to increase long before our core temperature does, as we pump blood to our skin. And while eclipsing these limits isn’t necessarily the worst-case scenario, prolonged exposure can become serious for vulnerable populations such as the elderly and people with chronic illnesses.

Our experimental approach has now focused on testing older men and women, as even healthy aging makes people less heat tolerant. The increased prevalence of heart disease, respiratory problems, and other health problems, as well as certain medications, can further increase the risk of harm. Some are over 65 years old Between 80% and 90% of heat wave victims.

How to stay safe

Staying well hydrated and looking for areas to cool off, even for short periods, is important in the heat.

While more cities in the United States are expanding cooling centers to help people escape the heat, there will still be many people who will experience these dangerous conditions with no way to cool off.

Even those who have access to air conditioning may not turn it on because of the high cost of energy – a common occurrence in Phoenix – or because of large-scale power outages during heat waves or wildfires, as is increasingly common in the western US

All in all, the evidence continues to mount that climate change is not just a problem for the future. It is one that humanity is currently facing and must address head on.

This article is republished from the conversationwhere it was updated from an article originally published on July 6, 2022.

Trending news

[ad_2]

Source link